Introduction

On November 16th 2021, the OK Europe trip around Europe brought Fondazione Feltrinelli to the modern heart of the old continent, Brussels. We started with the investigation of Vincenzo Genovese exploring borders, inequalities and perspectives of the capital of Belgium, home of the picture-perfect palaces of the European institutions, as well as crossroads of people and identities. This city provided the ideal setting to host a broad and inclusive discussion, raising the ever-so salient question:

what kind of Europe between technocracy and populism?

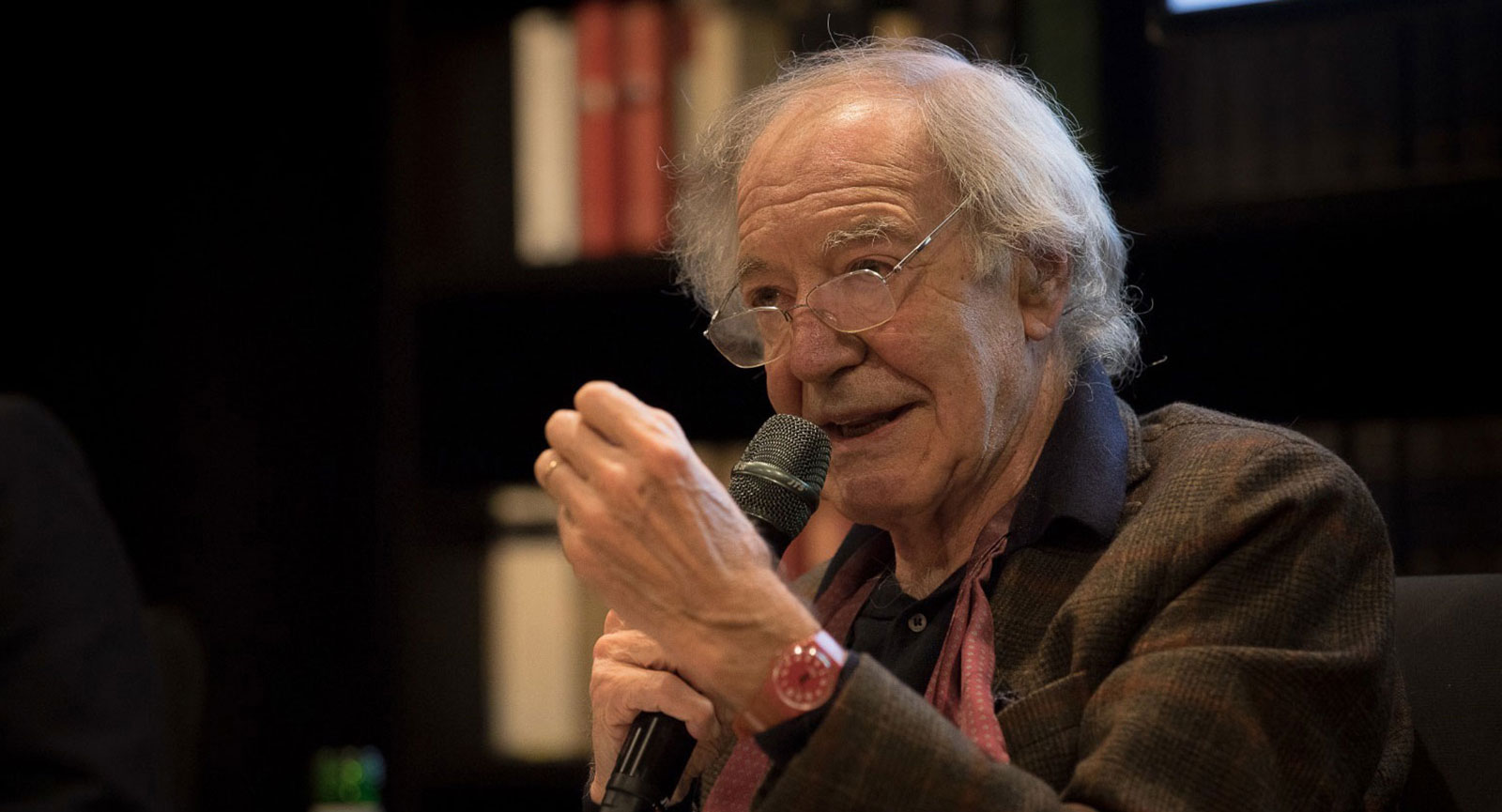

A dozen individuals with different backgrounds and experiences sat together around a table to discuss the question at stake. The bunch included academics, members of civil society organizations, trade unionists, think tankers and representatives from the European Commission and Parliament. Professor Colin Crouch opened up the discussion as keynote speaker, providing the group with its peculiar take on the matter.

Premises and keynote speech: identifying challenges and topics

The conversation kicked off with the difficult task – mainly performed by researchers from Fondazione Feltrinelli and Professor Crouch – to outline the most relevant challenges that European democracies are currently facing. Globalization was identified as the principal root cause of the ongoing crisis of representation and participation. The strong asymmetry between political and market powers has led to a general reduction in national political actors’ power to manoeuvre against supra-national financial constraints, ultimately negatively affecting the accountability and responsiveness of politics to the electorate.

These processes have also coincided with the crisis of traditional mass parties, increasingly uncapable to transform people’s social identities into political ones. Most voters do not feel the need to be loyal to political parties anymore and the latter, in parallel, are more and more detaching from their electoral bases. Twentieth-century cleavages, like religion and class, had allowed people to know precisely who they were and hence to easily identify which party could have stood up for them. Nowadays, old forces have markedly declined and new cleavages are emerging, pitting winners and losers of globalization against each other. While all of these processes affect mostly national democracies, they have also resulted in the weakening of the democratic legitimacy of the European Union.

If political representation seems to be occurring in the void of participation, in turn participation often happens without representation. People tend to mobilize over polarizing mono-issues, facilitated by the raise of civil society organizations and grassroots movements, as well as by democratic innovations, such as deliberative or participative assemblies.

In his introductory speech, Professor Crouch also identified some key trends connotating the status-quo of democracy in Europe. One is the raise of challenger anti-establishment parties, exploiting the perceived malaise of people, while also promoting nationalism and xenophobia.

Also rising are green movements and parties and feminism, which unite people against discrimination and injustices, much like class used to do.

Other noteworthy trends affecting traditional democratic dynamics include the political role of cities, the popularization of post-neoliberal discourses and changes in political communication allowed by the advent of the technological revolution.The debate with participants: key areas of action and best practices

In an almost three hours long discussion, participants to the workshop put forward their ideas, proposals and points of view to address the complex challenges ahead of European democracies, providing also examples of concrete practices, experiences and policies. The outcome was unanimous: avoid unanimity, or – in the words of one participant – “let’s not agree for once!”. There was in fact a strong call to value each individual viewpoint, preserving nuances and refraining from the impulse to over-simplify a plurality of voices. That is why, instead of proper recommendations, the group came up with a list of shared priority areas of action. The latter can be clustered in two sets: those pertaining top-down representation and those having to do with bottom-up participation.

With respect to representation, different participants pointed out the significance of having due institutional settings to avoid people’s disconnection from their representatives. At the European Union level, representation is undermined by the excessive reliance of the legislative process on a non-elective body, the Council. This exacerbates the ongoing depoliticization of policymaking and, as such, it should be reformed. Moreover, European politics also needs to better portray open societies as capable to deliver well-being.

Another key area of action identified was the responsiveness of politicians. “They promise the moon and then they give you a rock” stated one of the participants.

People’s expectations of politics are now extremely low due to the tendency of policymakers to not deliver on their promises. Leaders seem anthropologically unable to take seriously many of the challenges faced by ordinary people. A possible way out of this problem may consist in improving the suboptimal conditions under which political decisions are normally taken, promoting approaches that are much closer to how humans really think and decide. Another priority that was brought up during the workshop was reconnecting political parties with hesitant voters by understanding the reasons behind hesitant stances and moving away from polarizing narratives. Also important, although partially controversial, would be to include populist parties in the governmental arena as a way to ensure that their supporters are channelled in the system, in spite of leaning towards extremist perspectives. Finally, some participants also highlighted the need to overcome the paradox of participation, that is the idea that although everyone can participate, only those who have enough time, education or money actually do so.

Some best practices emerging from the debate:

The Conference on the Future of Europe: Initiated in March 2021 through a joint declaration by the three European institutions, the Conference on the Future of Europe is a participative exercise, involving citizens, as well as governmental and non-governmental stakeholders, in a discussion regarding the European Union’s future challenges and priorities. In order to reach a conclusion by spring 2022, a Multilingual Digital Platform interactively involving citizens has been set up and a set of conferences and debates will be held in various Member states.

Enlightenment 2.0: A research project by the European Commission Joint Research Centre, Enlightenment 2.0aims to understand the drivers of political decision-making. At its core, this project strives to improve policy-making conditions, by promoting a human-centric approach to political behaviour beyond rationality. Other areas of interests for the project include technologies and values.

When it comes to participation, one of the most relevant topics emerging from the discussion was the representative power of civil society organizations. The latter would be in a privileged position when it comes to channelling people’s political interests. However, for these stakeholders to be truly impactful, civil dialogue should be strengthened and better embedded in policymaking, at least as much as social dialogue is. Then, if appropriately upscaled, civil society organizations could become suitable platforms to facilitate the connection between people and institutions. Furthermore, social and human scientists could also be invited more to participate to policy discussions, contributing with their specific knowledge to mediate between realities and politics. Despite the importance of stakeholders’ engagement was widely recognised, some voices in the workshop underlined how participation itself is often relegated to a minority of specialists, constituting another elite that is far away from citizens. Therefore, the importance of other forms of bottom-up engagement also surfaced from the discussion, including deliberative and participative practices. Across the board, workshop attendees agreed that to elicit actual changes in people’s institutional trust, citizens’ fora need to be empowered and made transparent, avoiding “gamification”. Moreover, participatory practices should address political issues that have actual relevance for the people involved and enough time should be allocated to allow participants to immerse themselves in these experiences.

Some best practices emerging from the debate:

Right2water: The first European Citizens’ Initiative was launched in 2012 by public service unions, with the view to fight the liberalisation of water services and to guarantee access to water and sanitation in Europe and across the globe. European Social Initiatives indeed allow European citizens to play a role in setting the Unions’ agenda, as long as at least one million signatures from seven EU Member States are collected. Right2water has almost doubled this figure and so the European Commission was prompted to – at least in part – acknowledge its demands in the Drinking Water Directive.

Wijkbudget Gent: In 2020, the city of Ghent in Belgium launched a project that represents an interesting example of liquid democracy at the local level, where citizens can actually feel like their participation matters. Wijkbudget Gentasked locals to share on the municipal webpage ideas about how to improve their neighborhoods. Neighborhood panels and tables of dialogue with the public administration were also set up. All in all, the idea was that, to be financed with the city budget, any project would need to be supported by the inhabitants that it affects.

With the rising inflation and the cost of living rapidly increasing in most countries, the issue of compensation becomes crucial for the majority of workers. A promising initiative in this respect comes from the European Commission, which has recently proposed a Directiveon Minimum Wages (currently being discussed by the co-legislators).

This proposal has been received negatively by a number of opposing countries (including Italy), maintaining namely that a national minimum wage would decrease unions’ power in participating in collective bargaining. Nonetheless, the available literature on wage distribution and union participation suggests that the Minimum Wage Directive represents a promising policy intervention, which could improve the work of many European citizens.

A final and transversal key area of action identified in the workshop was the need to deepen and mainstream narratives resonating with current social identities, such as ecofeminism and social justice. Attention to these narratives would allow to move the political debate away from identity polarisation towards issue polarisation. Related to this, workshop attendees also called for parties and civil society organizations to foster inclusivity, thus ensuring diversity, as well as gender and generational equality. These organizations would indeed have a duty to “lead by example”, hence to implement to their internal structures and strategies the transformations they advocate for externally.

Conclusions: 3 messages

Summing up a dense exchange, the group ultimately put forward three messages, comprising the key areas of action outlined above, in hopes that they could be useful to guide policymakers, stakeholders and citizens in bridging the gap between representation and participation:

- politics should be re-politicized to overcome the erosion of responsiveness and accountability of representative bodies and to make sure that these effectively deliver on their promises;

- new forms of participatory networks need to be relied upon and civil dialogue should be strengthened to create a political environment that welcomes compromises and differences of opinions;

- parties and stakeholders need to lead by example, first, by mainstreaming new social narratives in their demands; and, second, by making their own internal structures and strategies inclusive.

Participants:

Ioana Banach, Green European Foundation

Kelsey Beltz, The Good Lobby

Brando Benifei, Member of the European Parliament (Socialists & Democrats group)

Mathieu Berger, Université Catholique de Louvain

Colin Crouch, University of Warwick

Alva Finn, Social Platform

Magda Herbowska, European Commission Joint Research Centre

Paola Maniga, Fondazione Feltrinelli

Sara Mondonesi, The Good Lobby

Leonardo Puleo, University of Thessaloniki

David Rinaldi, Foundation for European Progressive Studies

Pablo Sánchez Centellas, European Public Service Union

Maria Giovanna Sessa, Fondazione Feltrinelli

Marianna Stori, Fondazione Feltrinelli

Davide Vittori, Université Libre de Bruxelles

In collaborazione con